What’s In a (Domain) Name?

I recently exchanged some tweets with someone who was trying to update her organization’s web site but didn’t have sufficient access to do so. She had a pretty good grasp of what she needed to accomplish but was being blocked at every turn. It made me think that, while modern site building tools have brought online publishing to the masses, there are still many management functions that require an understanding of how web sites and, indeed, the Internet as a whole, works.

I thought this would be a good opportunity to update and recycle a post that I published in 2008 and again in 2010 about that most basic building block of the Internet, the domain name.

Master of Your Domain

Every business and many individuals need their own domain name. This unique alpha-numeric address becomes the name used to identify you in a web site URL or an email address. The great things about a domain name are that 1) you have the right to use it exclusively and 2) it is portable anywhere on the Internet. You keep the same identity, regardless of which Internet Service Provider (ISP) or hosting company you use. There is however, a lot of confusion about how to register and then use domain names, as well as their actual function in the structure of the Internet.

Why a domain name?

Every computer on the Internet (even yours) has an address and, being machines, these addresses are numeric. They are referred to as IP Addresses (for Internet Protocol) and they are written in dotted-decimal notation; four numbers, each ranging from 0 to 255, separated by dots (e.g. 147.132.42.18). Even in the early days, when the Internet was used mainly by computer scientists and academics, they realized that referring to everything on the Internet using dotted-decimal notation was not going to fly. So a system was devised to use a domain name interchangeably with its IP Address. In other words, a domain name is a pointer to an IP Address.

Every computer on the Internet (even yours) has an address and, being machines, these addresses are numeric. They are referred to as IP Addresses (for Internet Protocol) and they are written in dotted-decimal notation; four numbers, each ranging from 0 to 255, separated by dots (e.g. 147.132.42.18). Even in the early days, when the Internet was used mainly by computer scientists and academics, they realized that referring to everything on the Internet using dotted-decimal notation was not going to fly. So a system was devised to use a domain name interchangeably with its IP Address. In other words, a domain name is a pointer to an IP Address.

In the beginning (and up until 1998), all domain names were registered and maintained by a single entity, called InterNIC (Internet Network Information Center). It was a fairly technical (and expensive) process to use but it had the advantage of being orderly. After that, the business of registering domain names was semi-privatized and domain name registrars began sprouting like mushrooms. The best news about this was that prices dropped drastically. The bad news was that many of them were no less confusing to use, some adopted predatory business practices and others went out of business in relatively short order. But love them or hate them (and I know of few people who love them), the domain name registrar is the first stop in acquiring your own domain name.

Note that many hosting companies (i.e. companies that provide web site and email services) are also domain registrars. You can often get a package deal for domain name registration and hosting services but it is not required that you use the same company for both functions. Where ever your domain name is registered, make sure that you retain control over the domain name record (see below).

What’s in a name?

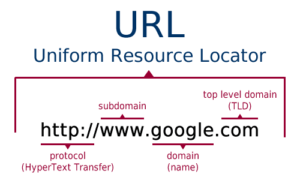

This is the last bit of technical information, I promise. Every domain name ends in a top-level domain (TLD), the letters after the last dot. The most common TLDs are .biz, .com, .edu, .gov, .info, .int, .mil, .name, .net and .org. You can use any of these TLDs in your own domain name, except that .edu domains must be registered by educational institutions and .mil domains are reserved for the U.S. military.

This is the last bit of technical information, I promise. Every domain name ends in a top-level domain (TLD), the letters after the last dot. The most common TLDs are .biz, .com, .edu, .gov, .info, .int, .mil, .name, .net and .org. You can use any of these TLDs in your own domain name, except that .edu domains must be registered by educational institutions and .mil domains are reserved for the U.S. military.

There are other TLDs, such as two letter country codes and those that are privately administered (such as .mobi, for mobile devices) but these are beyond the scope of this post.

The portion of the domain name before the last dot is where you can get creative. However, you are restricted to the letters a-z (case does not matter), the numbers 0-9 and the hyphen. Spaces are not allowed. This part of your name must be unique across the entire Internet. It has long been true that there are no English, single-word domain names available for registration. If there is one that you must have, you may be able to buy it from its registered owner, as transfers are allowed. If you owned a name like fund.com, you too could sell it for $10 million.

You may have noticed a second dot in some domain names. The name before this dot is called the sub-domain. These names do not need to be registered, since they are guaranteed to be unique by being attached to your primary domain name. Sub-domains are used to divide domains into logical areas, like a web site, a blog or a media server. The most common sub-domain is “www” and this is usually aliased to the same IP Address as the primary domain name. Note that sub-domains require configuration in your domain’s DNS record and that’s the next step in the process…

Don’t you hate it when people lie to you?

I know I said there would be no more technical stuff. You believed that? When you register a domain name, you fill out a bunch of information that becomes your domain name record. This record is held by the domain name registrar and you should have access to this record. Now listen to me: make sure you have (and keep track of) the username and password that gives you access to your domain name record. It can be a huge pain if you don’t have access to this record when you need it (like when you decide to move your web site and email to a new hosting company).

A very important part of your domain name record is the location of the nameservers for this domain. A nameserver is a computer on the Internet running DNS (Domain Name System) software, which is usually operated by an ISP or hosting company. Its location is expressed as a domain and subdomain (e.g. ns.hostingcompany.com) and there are usually at least two of them, for redundancy. Its purpose is to resolve domain names to IP addresses. If a nameserver cannot resolve the address locally, it will search other DNS servers for the correct record, a process called DNS recursion.

For each function that your domain will perform (web site, email, sub-domains, etc.) there will be one or more records in DNS, on the nameservers specified in your domain name record. Don’t worry, you should never have to deal with these records directly but your ISP or hosting company will.

If you decide to change the location where your web site and email are hosted, the location of these nameservers may also change. See why it’s important to have access to your domain name record?

Where to register

There are two types of registrars: those who are accredited by ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) and everybody else. There are several hundred accredited registrars worldwide and thousands more who resell though them. For what it’s worth, I use Namecheap.com as my registrar, although I don’t use them for any other services. I find their prices reasonable (about $10 per year, depending on TLD type) and I like their administrative interface for managing multiple domains. They also hit you with a minimal amount of up-selling, making the buying process much more pleasant than most registrars.

Conclusion

Registering your domain name independently from your hosting provider gives you the most flexibility when setting up Internet services. Your domain registrar and hosting company or ISP work together but need not be the same company. When you purchase a domain name, its domain record resides with the registrar. Within that record is a list of the nameservers that have knowledge of your domain name and the corresponding IP addresses of the computers on which your various domain services are hosted.

References:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_name

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_Name_System

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain_registrar

Image by India 7 Network

My colleague Liku recently put together a pretty comprehensive piece on registering a domain. There is a ton of information out there; our guide was designed to cut through the noise a bit.

The post is here: https://www.cloudwards.net/how-to-register-a-domain-name/